The American Dream

December 10, 2021

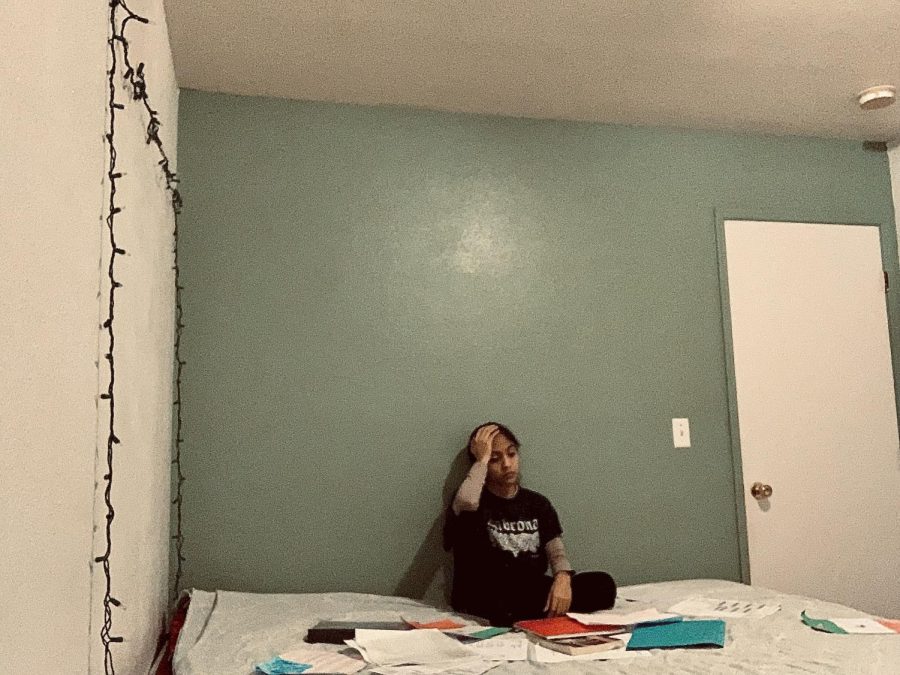

Seventeen. Senior. This is a place I’ve longed to be in for so long, yet now that it’s here I’m stuck.

“Where are you going to college!” they exclaim as their eyes force me to lie and claim whatever major it is that I feel is appropriate at the moment.

“Political Science.” “Journalism.” “Music.”

These are the big little lies that follow me around each day.

My family moved to The United States when my sister was only two, and my parents had only her as a symbol of their pride. Much like other immigrants, they came here not in search of a better life for themselves, but rather for their daughter and future daughters to come. It was a good enough reason really, but no good deed goes unpunished.

Neither of my parents ever finished high school, let alone go to college. As a result, it was instilled in me from a very young age that school was the most important accomplishment one could have. They watched as their two older daughters flew out of the nest only to fall a few moments later.

As the youngest daughter, I have often faced the burden of being compared to my sisters. At first glance this should not be an insult. Monica is a delight, her hands flowing with creativity and life. Claudia is a beauty as she comforts even the demons sleeping in the dark. Yet I am neither of them. I am Victoria, representative of victory. But if such a thing is true, then why do I feel defeated?

The delight and the beauty that were my sisters, could not make our parents proud in the way they felt they deserved, therefore, the spotlight turns to me. It is now my responsibility to give my mother the college degree she never received. But this is not a spotlight I ever wanted or even was supposed to have.

My entire life I have felt guilty because of the pressures that have been placed on me by both my parents and my siblings. Yet I take a small amount of comfort in knowing I am not the only one.

Many first-generation students feel academic pressure and worse, academic guilt. My parents could not afford to go to high school and yet I have the impertinence to complain about a free public school? Why do I have the audacity to complain about the dress code, the college board, the standardized testing, when “America” is an opportunity my parents did not have? Perhaps it’s because despite feeling guilty for getting everything my parents wish they had in life, I can see the flaws in this magical place that my people call “El Norte.”

As a little girl, I believed that someday I would become a lawyer. This was, of course, after I discovered that blood repulses me therefore I could not be a doctor. I believed that one day I would sit in the Senate and run for the presidency. These dreams however, did not last, for they were not mine to own.

Many students feel the guilt that their immigrant parents have unintentionally placed on them. As a result, they resort to choosing STEM majors that they perhaps did not want. They do it to make their parents proud, and to live up to this image of what a good little immigrant is.

I was born in the United States. I was delivered by an “American” doctor and given an American birth certificate. Yet in the eyes of bigotry, I will always be an immigrant, and because of this, I have to try ten times harder than everyone else, and fail ten times worse.

I am now a senior in high school and I’ve lost all of the plans I’d previously laid out for myself. I can’t be a lawyer if I must defend people I disagree with. I can’t be a professional musician without losing my passion for music. And I can’t be a journalist if I want to lavishly afford living in a big city, far from the reach of this provincial little town.

The American Dream is the dream that allows people like my mother to hope for their children to one day have what she does not. But the American Dream does not account for the disparities between first generation children and the white kids whose families have been here for centuries.

My American dream will someday allow me to be free from the pressures that society places on children of immigrants. So one day I won’t be afraid of questions revolving around my academic life and future career path.

“So what do you plan on doing with your life?” they’ll ask.

And I can respond with, “I simply do not know.”