Many students across the country’s secondary education system aspire toward higher level institutions with the promise of access to research opportunities, building on the successes of previous generations. They seek to develop new, innovative technologies to better the wellbeing and general standard of living of society, whether it be through fields such as engineering and software programming or in educating the next generation. However, few fields seem as significant yet unattainable as healthcare.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, there were 3.1 million Americans between the ages of 16 and 24 who graduated high school in 2023. Of these, only about 1.9 million enrolled in postsecondary education, or about 61.4 percent. The path to medical school only narrows from there. The American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) claims only about 55,188 college students applied to medical school during the 2022 to 2023 admissions cycle. Only 22,712 were admitted. That means roughly 41.15 percent of applicants were enrolled in a medical school. However, consider that the average student sent approximately eighteen applications.

Med School Insiders reports some of the acceptance rates into graduate medical programs of the “more prestigious” institutions, like Stanford University, Harvard University and the University of Virginia. In aforementioned order, their rates in 2022 were as follows: 1.1 percent, 2.1 percent, 2.5 percent.

Postsecondary students aspiring to enter the healthcare industry are advised often to apply to about fifteen programs, according to The Princeton Review, but it is recommended they send applications to over twenty if they reside in competitive states like New York or California. Yet, the fees are unrelenting. The AAMC asserts that the cost of applying in 2025 will be $175 for the first program with another $46 for every other. Assuming someone applies to twenty graduate schools, this would augment to $1,049, and the national average, as aforementioned, was approximately 41 percent admissions rate.

The Oracle explains that the United States is “experiencing a severe shortage of workers at every level” of the healthcare system. The American Hospital Association predicts that, by 2033, there will be a need for 124,000 physicians. Duquesne University claims that by next year, 2025, over 400,000 home aides will be in need, in addition to 29,400 nurses. In January of 2024, says Statista, there were a mere 1.1 million physicians in the country. So why, then, are medical school acceptance rates so low during a time of urgent need?

The American Medical Association (AMA) claims many of the acting physicians serve more time as instructors of medicine than in patient care. Yet, according to the National Association of Community Health Centers, the current shortage signifies about 30 percent of Americans do not have a primary care physician.

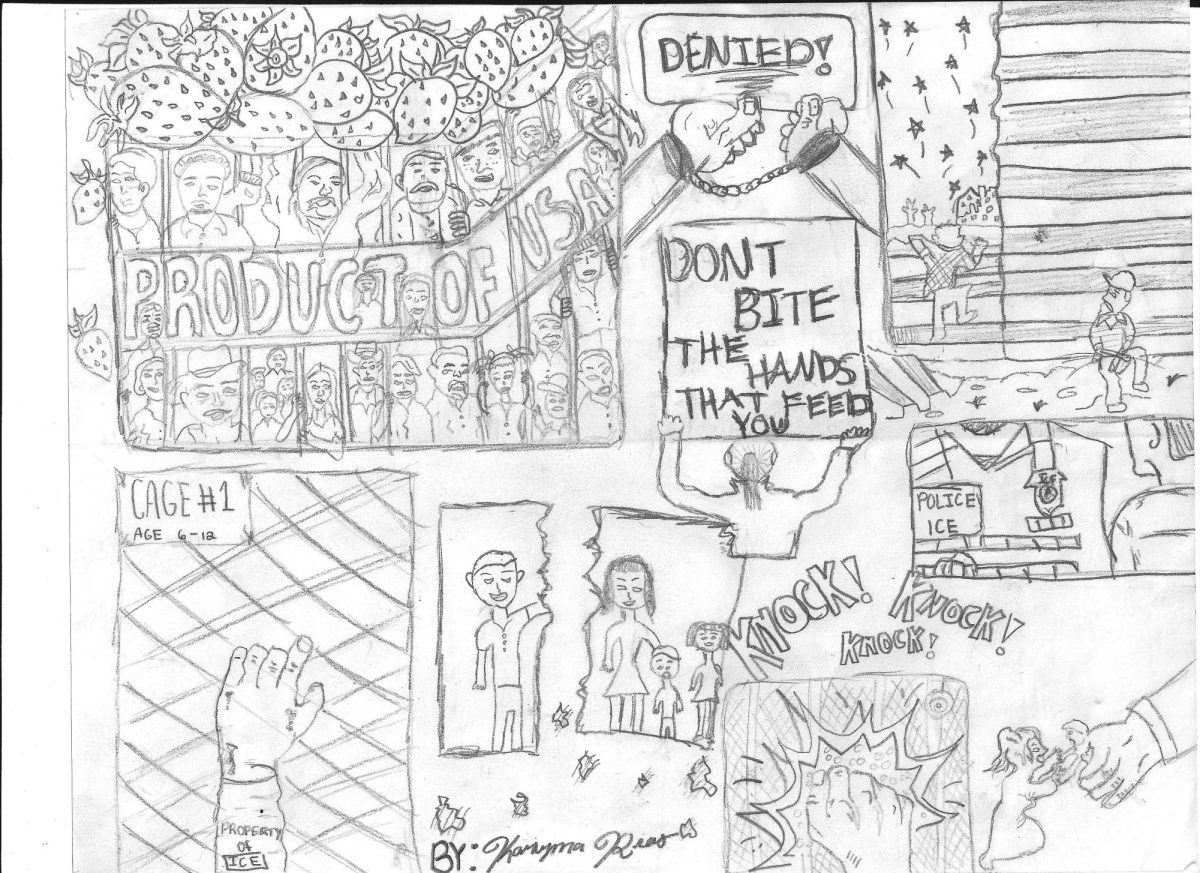

US News and World Report argues that the chronic decline in acting physician numbers have led to a lack of available instructors at medical schools, and that in admitting more students, the quality of education would diminish. In that case however, more government funding should be devoted to improving the accessibility of these graduate programs, which are vital to the prosperity and wellbeing of the nation. The United States has long been a location of immigration for foreign nationals. The influx of educated physicians abroad should be encouraged through increased benefits if they are willing to act as professors to train hopeful doctors. In 2021, according to the AAMC, about 200,000 active physicians had attained their medical degrees from other nations, where they had been born and raised, and traveled to practice in the United States. If there is hope for the healthcare industry, it lies in these individuals who are numerous and qualified. However, the bureaucracy of the current administrations which govern medical care are not appealing and will inevitably dissuade these saviors from bothering to immigrate.

Only days before November 3, 2024 for example, workers at the medical center of the University of California, San Francisco were preparing to go on strike. On that day however, according to the Microsoft Network (MSN), they actually voted to do so, citing lack of proper resources to maintain quality of care, such as insufficient staffing and space.

When international physicians, who contemplated traveling to the United States to open practice, get news of this, they will unequivocally be reluctant. Thus, the solution to the great struggle seems to lie in redirecting funding to improving working conditions to appeal to a wider range of individuals, encouraging foreign physicians to immigrate to the States, providing more incentives to doctors to train aspirants and generally increasing the acceptance rates of medical schools. Not over-significantly, but enough to allow a greater number of individuals who can reverse the trend of decreasing physicians.

In considering the aforesaid however, it may be permissible to also assert that requirements to enter medical school should be lessened, at least temporarily until the shortage subsides. Only in doing so, combined with the earlier conditions, can the nation commence recovery from this chronic issue which has long plagued the populace in depriving them of ease of access to healthcare.